I. Introduction

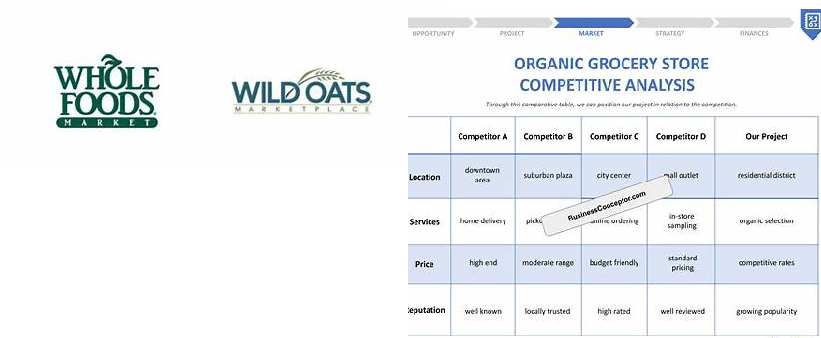

Whole Foods Market, Inc. announced a $565 million merger in 2007 to buy Wild Oats Markets, Inc., two of the best specialty grocery stores in the U.S. that sell high-quality natural and organic goods. The deal led to a long antitrust fight by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which claimed that it would significantly reduce competition in some local markets, which is against U.S. antitrust law.

II. Legal Framework

A. Clayton Act § 7

Section 7 of the Clayton Act says that mergers and acquisitions are illegal if they "may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly." ³ The law is intentionally forward-looking and probabilistic, which means that enforcement agencies can challenge mergers based on how they are likely to affect competition in the future rather than how they have already harmed it. ⁴

B. FTC Act § 13(b)

The FTC may ask for preliminary injunctive relief under § 13(b) of the FTC Act to stop permanent damage to competition while administrative proceedings are going on. ⁵ In these cases, the FTC doesn't have to prove ultimate liability; instead, it just has to show that there is a good chance of success or, as the D.C. Circuit put it, "serious questions going to the merits," and that the balance of equities favors injunctive relief.

II. Procedural History

In June 2007, the FTC sought a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to block the transaction.⁷ The district court denied the injunction, concluding that the FTC’s proposed market definition was too narrow and that conventional supermarkets constrained Whole Foods’ pricing.⁸

The FTC appealed, and in 2008 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit reversed, holding that the district court had applied an unduly demanding standard and had improperly discounted the FTC’s economic and documentary evidence.⁹ Despite the merger having already closed, the FTC continued administrative litigation, which culminated in a 2009 consent order requiring substantial divestitures.¹⁰

III. Procedural History

In June 2007, the FTC sought a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to block the transaction.⁷ The district court denied the injunction, concluding that the FTC’s proposed market definition was too narrow and that conventional supermarkets constrained Whole Foods’ pricing.⁸

The FTC appealed, and in 2008 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit reversed, holding that the district court had applied an unduly demanding standard and had improperly discounted the FTC’s economic and documentary evidence.⁹ Despite the merger having already closed, the FTC continued administrative litigation, which culminated in a 2009 consent order requiring substantial divestitures.¹⁰

IV. Economic Analysis

A. Relevant Product Market Definition

The main economic disagreement was about how to define the market. The FTC said that the relevant product market was premium natural and organic supermarkets (PNOS), which are defined by:

A big focus on organic, natural, and specialty items;

A lot of good service in the store and a unique shopping experience; and

Pricing and merchandising plans that are different from those of regular supermarkets.¹¹

The FTC's theory was based on demand-side substitutability, which means that a large group of consumers would not switch from regular supermarkets to other stores if the price went up a little but stayed the same for a long time ("SSNIP").Internal Whole Foods documents that called Wild Oats its "only real competitor" gave this idea some qualitative support.¹³

The district court, however, focused on marginal consumers who might switch to conventional supermarkets, effectively broadening the market.¹⁴ The D.C. Circuit criticized this approach, emphasizing that antitrust market definition does not require exclusion of all substitutes, only that close substitutes are sufficiently limited to permit market power.¹⁵

B. Unilateral Effects

Economically, the FTC advanced a unilateral effects theory rather than a coordinated effects theory. Because Whole Foods and Wild Oats competed closely on price, quality, and location, their merger would eliminate direct head-to-head competition in numerous local markets.¹⁶

Under standard unilateral effects analysis, the elimination of a close substitute increases the merged firm’s incentive to raise prices or reduce quality because lost sales are more likely to be recaptured internally rather than diverted to rivals.¹⁷ The FTC argued that diversion ratios between Whole Foods and Wild Oats were high, making price increases profitable post-merger even without coordination.¹⁸

C. Entry and Expansion Barriers

The FTC also said that there were big barriers to entry. To build a supermarket like PNOS, you needed:

Access to supply chains that are specific to your needs;

Brand reputation among customers who care about quality; and

A lot of money needs to be invested and zoning approvals must be obtained.

From an economic perspective, entry that is untimely, improbable, and inadequate cannot undermine a merger presumption of anticompetitive harm. ²⁰ The FTC said that new businesses would take a long time to get started and would not be able to stop price increases after a merger.

D. Empirical and Documentary Evidence

The FTC did not base the case on just one econometric model, but on a mix of

Analyses of internal prices;

Documents for strategic planning; and

Natural experiments in which Whole Foods changed prices when Wild Oats came in or left. ²¹

The D.C. Circuit's readiness to accept this mixed evidence indicated that merger enforcement does not have to depend solely on formal econometrics when qualitative and documentary evidence robustly substantiates competitive apprehensions. ²²

V. Settlement and Remedies

In 2009, the FTC made a deal with Whole Foods that forced the company to sell 32 stores in 17 different markets, along with other assets and intellectual property, such as the rights to the Wild Oats brand. ²³ The remedy was meant to bring back lost competition by letting an independent competitor take the place of Wild Oats' competitive constraint. ²⁴

VI. Significance for Antitrust Law and Economics

There are a few important things about FTC v. Whole Foods:

Validation of Narrow Markets—Courts may acknowledge distinct retail formats as economically significant markets. ²⁵

Less Evidence Needed at the Injunction Stage— The FTC doesn't have to prove harm; it just has to raise serious questions about competition. ²⁶

Integration of Law and Economics — This case shows how qualitative evidence can add to formal economic analysis. ²⁷

Post-Consummation Remedies: Structural relief is still available after a merger has closed. ²⁸

VII. Conclusion

The Whole Foods–Wild Oats lawsuit shows that § 7 of the Clayton Act is still important for stopping anticompetitive mergers, especially in markets where there are many different types of products. The case has become a cornerstone of modern merger jurisprudence by combining economic reasoning with traditional legal analysis.

Footnotes

FTC v. Whole Foods Mkt., Inc., 548 F.3d 1028, 1032 (D.C. Cir. 2008).

Complaint ¶¶ 1–3, In re Whole Foods Mkt., Inc., FTC Docket No. C-4206 (2009).

15 U.S.C. § 18.

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 323 (1962).

15 U.S.C. § 53(b).

Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1036.

Id. at 1033.

FTC v. Whole Foods Mkt., Inc., 502 F. Supp. 2d 1, 15–16 (D.D.C. 2007).

Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1036–37.

In re Whole Foods Mkt., Inc., FTC Docket No. C-4206 (Mar. 6, 2009) (consent order).

Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1033–34.

U.S. Dep’t of Justice & FTC, Horizontal Merger Guidelines § 4.1.1 (2010).

Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1035.

502 F. Supp. 2d at 15.

Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1038.

Id. at 1034.

Merger Guidelines § 6.1.

Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1034–35.

Id. at 1037.

Merger Guidelines § 9.

Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1035.

Id. at 1036–38.

In re Whole Foods Mkt., Inc., FTC Docket No. C-4206.

Id.

Whole Foods, 548 F.3d at 1037–38.

Id. at 1036.

Id.

Id. at 1039.